Among the major lessons of the books of my childhood is that slang is very bad, and that it’s the central task of parents to cure their children of it. There is much handwringing over the use of informal speech, the kind of despair we reserve today for stalled potty training, profanity, bullying, drug abuse, and delinquency.

Take Eunice Young Smith’s dreamy Jennifer Hill, books published in the late 40s and early 50s about a character growing up in the early 1900s. Jennifer is fond of superlatives: “spiffy,” “spondolix,” and “scrumptious.” Their mother doesn’t quit approve of this. She keeps admonishing the children to say “surely,” instead of “sure,” “goodness,” instead of “gosh.”

Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne is aggrieved when young Davy of Anne of Avonlea, published in 1909, admires a “bully splash,” since bully is apparently a highly vulgar if enthusiastically complimentary adjective. 1880’s Little Women’s Jo likes to exclaim “Christopher Columbus!” but manages to finally overcomes this appalling habit. She is eventually praised by her father for no longer being his “son Jo.” He says, “I see a young lady who pins her collar straight, laces her boots neatly, and neither whistles, talks slang, nor lies on the rug as she used to.” Jo, the most critical of all heroines of female indoctrination, is also, paradoxically, the only literary heroine ever to be cured of using slang.

Poor Laura in Little Town on the Prairie isn’t reprimanded for slang, but what appears to be its close cousin, “wooden swearing.” In the book, published in 1941 but taking place in the late nineteenth century, Ma scolds her for this after an outburst against the pressures of having to study all the time in order to earn her teaching certificate at fifteen and provide her sister an education. Laura doesn’t swear, but her tone has suggested that she might possibly want to, and the mere possibility of this desire merits a reprimand. Even an all-too-human expression of exhaustion is too unladylike to be borne.

Even while her characters are perpetually reprimanded for their slang, Anne creator Lucy Maud Montgomery makes fun of the prudery that leads to euphemistic language, as in an argument in which Dora insists that a tomcat should be referred to as a “gentleman cat” while Davy maintains it should be a “Thomas pussy.” And in Anne of the Island (1915), when corrected for using the phrase “dig in,” Anne’s friend Phil laments, “Oh, why must a minister’s wife be supposed to utter only prunes and prisms?” Slang, she adds, is only “metaphorical language.” She then wisely concludes that she’ll be perceived as stuck up among the parishioners that her future husband serves if she doesn’t use their language.

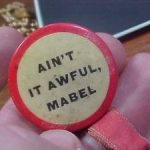

Thank goodness that slang wasn’t eradicated from the speech of all characters. Sometimes, it’s one of the quickest routes to recreating a time period. I remember one autumn night a few years ago, as a light cold rain fell and leaves skittered across the street, I dropped my daughter off at a school dance and went home to reread Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy books, set in the early 1900s. While my daughter was off at a middle school gym navigating a world of kids who casually said “WTF” at every turn, I was content at home with a bunch of teenagers whose favorite slang is “Ain’t it awful, Mabel?”

The period slang is one of my favorite things about Lenora Mattingly Weber’s Beany series. In Meet the Malones (1943), a bigshot football player takes an interest in Beany’s sister Mary Fred. Dike—yep, that’s his name—prefers “smooth little queens” to “mop squeezers” like Mary Fred or to “studes,” girls who make good grades. But suddenly, wisecracking Dike resolves to make Mary Fred his “squaw.” Dike is clearly using Mary Fred; his trendy language announces his lack of substance, as does his unfortunate name, probably meant as an ironic reference to a hole in the wall that lets water through rather than any secret lesbian tendencies.

In Make a Wish for Me (1956), Beany’s boss, Eve, says, “In my day we called it ‘petting.’ And it did a girl no good to be labeled a ‘petter.’ You’ll notice, Beany, it’s always the girl who is labeled, never the boy. As I say, it’s a man’s world. What’s the word for petting now? I can’t keep up with it. Smooching?” Beany replies, “No, that’s baroque—meaning old-fashioned. Now it’s loving-it-up. Only at Harkness we have a new word—more-thanning. . .” Nowadays, more people remember terminology like petting and smooching than loving-it-up and more-thanning. Most of this slang had largely fallen out of use by the time I encountered these books, replaced by necking and then making out. Today, people hook up rather than loving-it-up. They certainly no longer more-than, as far as I know.