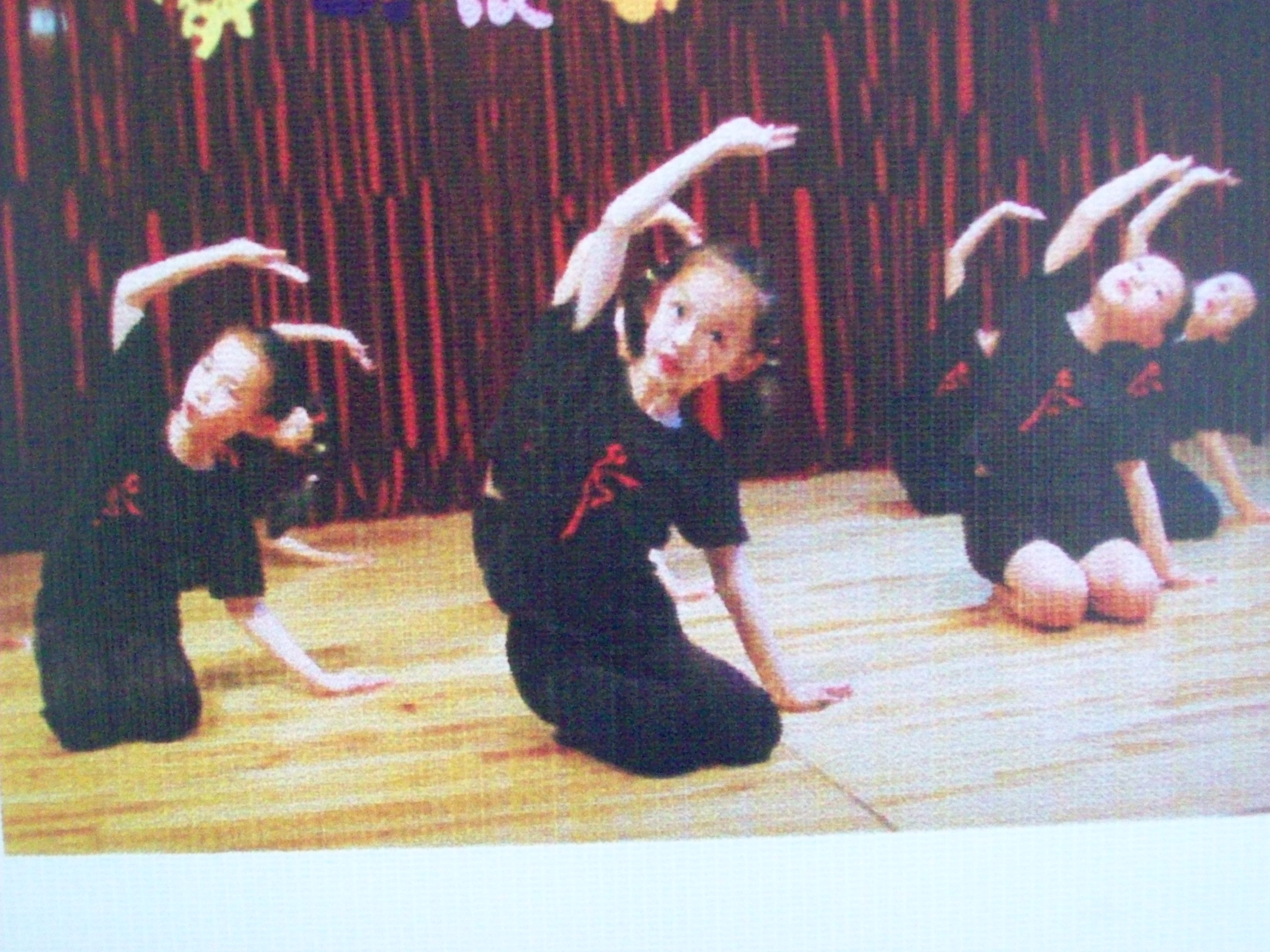

It’s our last day in Guilin, and I’m a little sad to be packing, making our last bus excursion to the botanical gardens, taking Sophie to her last traditional Chinese dance class, and saying goodbye to new friends today. I thought by now I’d be chomping at the bit, raring to get home, desperate for my own space and familiar foods, and I am looking forward to going home, but I’m also surprisingly reluctant to leave Guilin. Sophie, though, is downright resistant. As much as I wanted to honor her sense of connection to her roots, I guess there’s a part of me that hoped that an extended visit to China would get this country out of her system. But if anything, she’s more attached than ever.

“Sometimes I wonder, what are we doing?” an American dad of a Chinese-born adopted daughter said to me as we strolled around a lake the other day. “By encouraging our children’s interest in China, are we also encouraging them to leave us someday?” Because we do fear, a little, that our children will someday want to live here, that we’ll have to fly halfway around the world to see our grandchildren. Not all children from China are so curious and passionate about their homeland from a young age, but ours were. So we had a choice: stand in their way or clear their paths. We have chosen to clear their paths, though sometimes with trepidation about the consequences to ourselves.

But of course, our dilemmas are the dilemma of every parent: how much to hold on, how much to let go. And it’s amazinghow much the world has changed just in the last few years, how much smaller it feels, how different still it will be by the time our children reach adulthood. Twenty-two years ago, when my friend Sara lived and taught in China, handwritten letters in tiny print on thin aerograms were her only contact with the outside world, and for reading material her only English-language choices were Penguin classics from local bookshops.

Now, even visiting Guilin, regarded by the Chinese as a small town because its population is “only” about 700,000, is no longer such an isolated experience. We have e-mail to keep in contact with friends, made the dangerous discovery that we can still buy Kindle books here, and on the rare occasions that we missed TV or movies, went to the local cinema or picked up $2 movies to watch on the computer. It wasn’t quite the same eating dragon fruit instead of popcorn, since the only microwavable kind is sweet, not salty, but it was close enough.

Our routine has stayed pretty much the same as at home. Sophie has read eight books, learned some new games, and spent hours hanging out with girls in our building. I’ve kept up with writing projects, recommendation letters, long-distance advising, graduate student applications and packets, and page proofs for forthcoming publications—my normal summer work. The only difference is, as soon as we leave the apartment, I remember that I’m in China. We’re surrounded by high rises and gardens and honking cars and buses and motorbikes and the sound of people speaking Chinese. We’re both starting to recognize more words. We can put together a few simple sentences. It’s hard to leave just when that is happening, though the process will continue in Beijing.

And I won’t miss being stared at all the time, a phenomenon that is less common in bigger cities. One day Sophie and I made our way through brush down to a lake, where we happened upon a couple sitting on a rock, contemplating the water. Except then they decided to contemplate us instead. They turned to us and stared intently, faces expressionless, gazes unwavering. I smiled and waved but they remained completely immobile, like staring statues. At their feet, there was an overhead projector, half in the water. The water lapped at the screen and the couple stared at us and I thought, OK, there’s a beautiful ancient pagoda across the water and, for some reason, an overhead projector floating at your feet, and you’re staring at us? Shouldn’t we be the ones staring?

But Sophie even feels nostalgic about the stares. She admits that she misses friends, her dog, gymnastics, her violin, and tacos. But the loss of Guilin looms larger now than anything else. She can’t fully articulate what she’ll miss: “Rice noodles!” she says. “The maze.” She likes walking in the maze created from bushes outside our building, and looking down on them from our roof, and I have to admit that it’s cool, but really? She’s going to miss that?

“The buses,” she says, “the streets, the food, the people, Aiyi.” “Aiyi” means “Auntie,” our housekeeper, cook, and friend. And then her list becomes highly suspect: “The heat, the humidity, the comforter,” she says. “I’ll miss the comforter.” In China, even in tropical regions like this one, we have never encountered a thin sheet or blanket. For some reason, the beds have heavy comforters. And I’m sorry, I do believe that we’ll miss Aiyi, but the heat, humidity, and comforters?

Sophie dug in her heels when it was time to leave Beijing three years ago and again when we left Barcelona two years ago. So maybe this is more about the lure of foreign places than it is about China. But I don’t know. I only know that I used to think I could make a list of places that I wanted to visit, and once I’d traveled there, I could check them off and move on to the next. Our visit here was supposed to be a one-time thing, but Sophie already wants to know if we can come back next year. Probably not next year, I say. But as we head to Beijing to meet up with Pennsylvania friends and attend a language and culture camp, I have a feeling that we’ll be back someday.