I have low expectations for our visit to the social welfare institute in Yiwu where Sophie spent the first ten months of her life. The agency that made our arrangements doesn’t have a lot of contacts at the orphanages, many people have told me, and visiting families have been stonewalled, given no information, and denied access to the baby room and their children’s files.

I was surprised to hear this. Three years ago, another agency arranged for us what turned out to be a life-changing visit here. To our surprise, we ended up in a remote village, tracking down a wealthy local merchant named Mr. Lu who’d once taken a special interest in Sophie. We had lunch with him and his wife and were toasted by the town’s mayor. Later we found ourselves in another, even more remote village—what turned out to be Sophie’s birthplace, experiences I’ve written about in an essay forthcoming in Prairie Schooner and in my new book.

But after hearing others’ stories, our visit three years ago seemed like a fluke, as did the fact that I’d glimpsed a paper in Sophie’s file, a scrawl of characters that apparently contained information about her background that we hadn’t known. I didn’t ask for a copy at the time, since an employee seemed to be breaking a policy by letting me see the file at all. Now, the orphanage has new administrators, and getting a copy of this paper seems like even more of a longshot.

Sophie keeps pointing out that when you don’t speak the language, everything feels abrupt. With no warning, everyone jumps up and troops off to a noodle shop at 10 p.m., or rushes out and hops in a van and the next thing you know, you’re in your birth village. You frequently find yourself doing things you haven’t planned, and much of the time, you have no idea what’s going on. So it is par for the course when we arrive at the SWI and instantly see a familiar face—Mr. Lu bounds down the stairs, his wife behind him, leveling their hands to comment on how much Sophie has grown. Our first request has been fulfilled—they have come to see us. A former staff member, Mr. Feng, who helped us locate the Lus three years ago, also makes a special trip to say hello, and the conference room fills with people, the new director and assistant director, our driver and guide, the Lus, Mr. Feng.

And then we all jump up and go off to the baby room, another surprise, another request fulfilled. It has changed considerably in three years. Now, healthy children have been sent to foster care. Domestic adoption is encouraged by the government and the one child policy has been slightly relaxed. Now the children in institutional care are mostly disabled. Toddlers scoot around in beat-up bouncy seats and line up in wooden chairs to watch “Teletubbies.” They jump up to wave their arms and dance. This room is bare and stark and hot, and there are no toys anywhere. I don’t know what happened to the many crates of toys we donated. Maybe they have all worn out.

Toddlers grab at our legs and our hands. One girl with severely scarred skin wants me to pick her up, but when I do she goes all limp and floppy. Like Sophie when I met her, this girl, at least two or three, doesn’t know how to be held. She is very bossy and tugs me around the room. At one point she calls me “Mama.”

Babies lie listlessly on the bare boards of their crib beds, a baby with albinism with a shock of pale hair, his whiteness startling among all of these other Chinese babies. Babies with enlarged heads, babies with crossed eyes, a baby whose top lip is folded back like a blossom before it opens to sunlight, whose eyes are curious and who laughs when I carry him and talk to him.

“Will these babies be adopted?” I ask our guide, and he looks confused and alarmed, thinking that I want him to ask the director for permission to bypass the proper channels and just take a baby home. This is my first clue that he doesn’t speak much English, which becomes the main barrier to us finding out what we want to know. He’s confused when I ask him to inquire about the orphanage’s needs. Finally he finds out that they could use a sewing machine and more bouncy chairs, which we purchase later that day, such small donations to a place whose needs seem so large.

Back in the conference room, I ask the guide to request a copy of the paper in Sophie’s file. For a good twenty minutes, I reword my request and am told that there is no file, there is no paper, I have all of the available information. “Mom, give it up,” Sophie says when I try again and again.

Mom, give it up—a common phrase these days, the reason I didn’t inquire about what came with her meal two days ago and she ended up with ketchup drizzled all over her fries, the reason I rushed off without getting enough information about a train yesterday and we raced frantically along the platforms, not sure where to go.

This time, I’m not giving up unless I hear a firm refusal, but I’m worried: what if I somehow imagined this piece of information about Sophie’s past? That scrawled note, that visit to Sophie’s birth village suddenly feels like the moments before anesthesia sends you into a twilight sleep, like the moments when the lights are bright in the hall and the orderlies are wheeling you along and then it’s all gone, and you wake the next hour or three years later and whatever happened in that gap between then and now has utterly disappeared.

But I reword, gesture, pantomime, demonstrate, and explain until the merciful moment when understanding dawns on faces around me. Someone retrieves Sophie’s file, and I locate the note, and the assistant director makes us a copy, just like that. We don’t have time to visit Sophie’s birth village again. The driver isn’t even sure where to find it; it is even more elusive than Hangzhou has been for us. Sophie’s once-rural birth village is changing, disappearing, its people moving away, ponds replaced by high rises as it is gradually absorbed into the city’s edges. We will request a trip there next time. Our agency may not have a lot of contacts at the orphanage, but I realize that somehow, miraculously, we do, that our previous visit has paved the way for this one, and this one, in turn, will pave the way again.

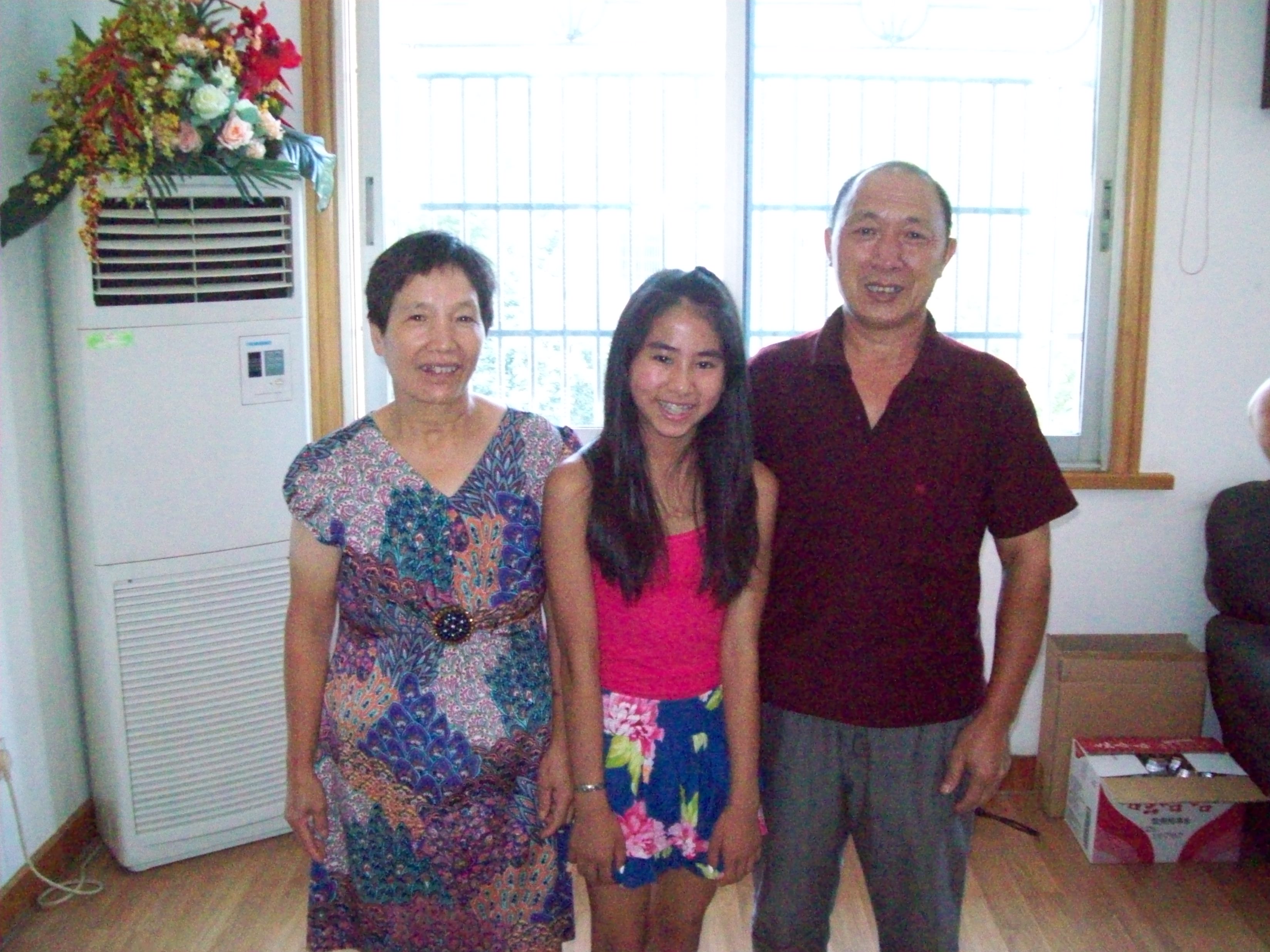

For now, we go to lunch with the Lus, able to communicate only through re-enactments of the past, of the way Mr. Lu brought me this baby on a train twelve years ago. I point at Sophie and imitate her, clutching at Mr. Lu, protesting: “Waaa, waaa, waaa.” Everyone laughs. Mr. Lu passes me his memory of the baby my daughter was, and I pretend to take her while he wipes a memory of tears from his eyes.