For my entire adult life, I hauled my collection of childhood books from state to state, house to house, never rereading them. Their mere presence was gratifying, each packed shelf like a neighborhood full of houses in which I’d once lived. But finally, when my daughter was a toddler, I returned to some of my old favorites, books I thought I might someday pass on to her.

I started, somewhat randomly, with Requiem for a Princess by British children’s writer Ruth Arthur, a book I recalled only vaguely. The jacket blurb of Requiem for a Princess said that it was about a girl named Willow who dreams the whole life of a seventeenth century occupant of the estate Penliss. It had all of my favorite childhood ingredients: heroines who want to be pianists or dancers or painters; gothic mansions by the sea; the turmoil wrought by an uncovered secret; the healing powers of nature. Eagerly I set forth, gradually deflating.

The story was flat and rushed and summarized. Where were the crusty bread and goat cheese, the rice pudding and sweet milk, the snowdrops and crocuses and jonquils, the fresh air and sunshine, all of the lush detail of children’s books in the nature-heals-all-tradition? Books like Heidi and The Secret Garden and Understood Betsy, populated by pale weak children transformed to strapping, healthy ones, described in a complimentary, joyful way as fat, with brown skin and red cheeks? And what’s the point of setting a book by the sea without crashing waves, misty spray, sand that pulls each step down so deep that you have to yank your feet free?

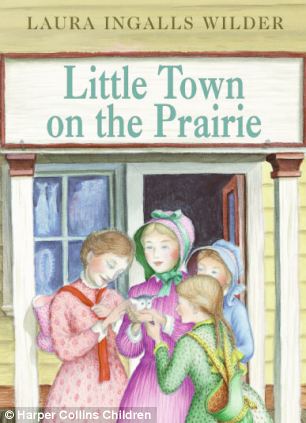

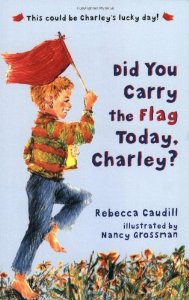

Though I was disappointed, I kept on rereading: the first chapter book I remembered checking out of the Wichita Public Library, Carolyn Haywood’s B is for Betsy; the first chapter book I’d checked out of the Seltzer School Library, Did You Carry the Flag Today, Charley? Classics I’d regularly received in the mail from the Children’s Book of the Month Club, books about big noisy families and stories about the performing arts and series books, especially the ones about Betsy Ray, Beany Malone, Nancy Drew, Jo March, Anne Shirley, Laura Ingalls. I read, and memories unfurled like tightly-wound ribbons suddenly released. Used copies of books arrived in padded envelopes, and as I cracked limp spines, pages sizzled with familiarity, my synapses firing off like crazy firecrackers of memory exploding.

Though my worldview had been shaped by many, many books, none had influenced me quite as profoundly as Laura Ingalls Wilder’s, the first books my mother ever read to me. When I returned to them, I flew through the series, their gratitude for small pleasures infecting me. I began to think in Wilder’s language; everything was happy, cozy, pretty, snug, and sweet. And all of a sudden, I was seized by an impulse to explore the woods above our house.

I was much more excited about this than my daughter, who was eight. It was 90 degrees, and she immediately started complaining that she was hot and tired. The path climbed steeply uphill, scored with deep muddy ruts from four-wheelers. Every few feet, tucked back into trees, overgrown with weeds, old oil derricks stood like miniature windmills robbed of their blades.

We followed a set of cables stretching way up the mountain, ending at a small engine house, the whole contraption rusted over. Northwestern Pennsylvania was the U.S.’s chief oil producer from the mid-1800s until early in the twentieth century, when much of the country’s oil industry shifted to Texas. In the 1870’s, there were 4,000 oil wells in Bradford, nearly half the number of the town’s human population today.

The path plunged steeply downhill, blackberry thickets tangling along the edges where the trail flattened out. I wondered if we should turn back before we got lost, but we pressed on and suddenly found ourselves at a clearing where the whole town spread beneath our feet. Black rooftops with their brick chimneys descended the hill like stair steps. In the valley below, downtown rose up, a few seven-story buildings against the backdrop of the opposite hills.

Then the end of the trail spilled us out onto a street. Nearby, an eerie clanking repeated and repeated—an empty swing in a breeze? A child’s loose bicycle wheel? The noise was too rhythmic to be either. We crept toward the sound, ears perked for children’s voices among the steady clank, clank, clank. Sophie glanced at me, wide-eyed. We squinted through the trees, expecting ghosts. Instead we came upon a little oil rig, cables alternating as they creaked up and down.

Turning the corner, we found ourselves looking down on the roof of Sophie’s school. “We could walk to school this way,” I said. I pictured her tramping through the woods like a storybook pioneer girl. I imagined strolling with her through the stillness, watching the leaves change in the fall, feeling, under our feet, the earth turn hard and frozen, our footsteps marking white stretches of snow. The Little House series had reminded me what it was like to feel like a character in a book.

“Mmm,” was all Sophie said in reply to my half-cocked notion about walking this way every day.

One of the first lessons most of us learn as writers is about the power of detail to build worlds and evoke memory, but rereading childhood books brought that home to me even more forcefully. It was, it turned out, those details that most strongly tapped into my memory and had the power, even in adulthood, to incite my imagination and remind me who I once was. As I reread, I existed in a relentless state of déjà vu, long-forgotten details appearing like retrieved memories: the strains of a fiddle beside a campfire, the smell of the woods on a summer day, the taste of peppermint, a new bird whistle, a chair seat braided from yellow rags, the glimmer of the stars overhead.

(This blog was excerpted from McCabe’s forthcoming book, From Little Houses to Little Women: Revisiting a Literary Childhood.)